History

Credit: UN Photo Unique Identifier: UN7745134

Credit: UN Photo/ME Unique Identifier: UN7738105

Credit: UN Photo/Saw Lwin Unique Identifier: UN7745131

Havana Charter Conference

From November 21, 1947, to March 24, 1948, delegates from various countries convened in Havana, Cuba, for the United Nations Conference on Trade and Employment. The primary objective was drafting the Havana Charter. The decline in international commodity prices captured the attention of policymakers as early as the 1948 Havana Charter. Nevertheless, the Havana Charter and ECOSOC’s guidelines did not inaugurate a comprehensive framework to stabilize commodity prices; instead, they gave rise to a series of limited, ad hoc arrangements. This period was characterized by persistent debate and tension between producers and consumers over the need for commodity-specific stabilization measures. Developed countries generally advocated a targeted commodity-by-commodity approach to ensure that interventions remained focused and constrained to individual markets.[1]

[1] Kelegama, S. (2014). Gamani Corea and commodity price stabilization. In South Centre, A tribute to Gamani Corea: His life, work and legacy (pp. 42) South Centre.

UNCTAD I agenda to equitable trade systems

From March 23 to June 16, 1964, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) convened in Geneva, Switzerland. The conference marked a pivotal moment in international economic cooperation, focusing on addressing trade disparities and promoting sustainable development in developing countries.

The conference emphasized the need for a more equitable global trade system, advocating for reduced trade barriers and enhanced access to markets for developing nations. Led by Secretary-General Raúl Prebisch, the discussions resulted in proposals for a "new trade policy for development," aiming to narrow the economic gap between industrialized and developing nations.

Developing countries, through the Group of 77, highlighted the inequities in the global trading system, particularly the impact of price instability on primary commodity exporters. The conference proposed the establishment of international mechanisms to stabilize prices and secure fair trade for these nations. Though concrete action was not immediately taken, the discussions reinforced the importance of a collective, integrated approach to commodity trade issues.

The proceedings of the Council (UNCTAD 1964) recorded the following:

“Moreover, the terms of trade have operated to the disadvantage of the developing countries. In recent years many developing countries have been faced with declining prices for their exports of primary commodities, at a time when prices of their imports of manufactured goods, particularly capital equipment, have increased. This, together with the heavy dependence of individual developing countries on primary commodity exports, has reduced their capacity for imports. Unless these and other unfavourable trends are changed in the near future, the efforts of the developing countries to develop, diversify and industrialize their economies will be seriously hampered. 9. Deeply conscious of the urgency of the problems with which the Conference has dealt, the States participating in this Conference, taking note of the recommendations of the Conference, are determined to do their utmost to lay the foundations of a better world economic order.’’ [1]

If we read the above quote from 1964, it might seem that the world has hardly changed for the billions of commodity-producing smallholders in the developing world.

[1] Source: Final Act, Preamble, page 4. https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/econf46d141vol1_en.pdf (accessed on January 29, 2025)

UNCTAD II the early development to Common Fund

From January 31 to March 29, 1968, the UNCTAD II convened in New Delhi to address growing concerns over commodity price instability. While the concept of a Common Fund for Commodities was first mooted at this meeting, it was still in an exploratory stage and not yet formally proposed or structured. Discussions focused on stabilizing commodity prices, improving supply security, and identifying potential financial mechanisms that could support such efforts in the future.

The conference emphasized the structural disadvantages faced by developing countries, including volatile commodity prices and unfavorable terms of trade, and recognized the need for a more just and rational international economic order.

Integrated Programme for Commodities (IPC) and Common Fund

The principle of shared responsibility between producers and consumers was first introduced in the Integrated Programme for Commodities (IPC), which was proposed in 1974 and formally launched in 1976. From February 10 to 21, 1975, the UNCTAD Committee on Commodities to review and discuss the IPC as a policy document addressing commodity price instability. Parallel to the IPC’s establishment, the idea of a Common Fund (CF) emerged as its catalyst — a vital financial arrangement aimed at stabilizing and strengthening commodity markets through market intervention.

Resolution 93 (IV), adopted by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) in 1976, marking a major milestone in international commodity policy and laying the foundation for future commodity cooperation initiatives. This resolution endorsed the Integrated Programme for Commodities (IPC) — a comprehensive framework designed to stabilize global commodity markets and correct the structural imbalances faced by developing countries heavily dependent on commodity exports. Conceived as a cornerstone of the New International Economic Order (NIEO), the IPC sought to establish a series of International Commodity Agreements (ICAs) to stabilize prices, ensure fair returns for producers, and reduce the volatility that had long undermined commodity-dependent economies.

At the heart of the IPC was the creation of the Common Fund for Commodities (CFC), envisioned as the financial mechanism to support the implementation of ICAs and fund commodity diversification and development projects. Together, the IPC and CFC represented a transformative approach to global commodity trade, emphasizing cooperation between exporting and importing countries to achieve more stable, equitable, and sustainable markets. However, the vision of the IPC and the NIEO soon faced resistance from developed, commodity-importing nations, wary of constraints on market forces and shifts in economic power. As the global economy moved toward liberalization and deregulation in the 1980s, the IPC’s momentum waned. Yet, the determination of developing nations kept the dialogue alive, eventually leading to the establishment of the CFC in 1989 — a legacy of the IPC and NIEO ideals.[1]

|

New International Economic Order (NIEO) NIEO emerged in the 1970s, driven by developing nations seeking to address economic inequalities rooted in colonialism and historic trade imbalances. Commodities (agricultural products, minerals, and raw materials) were central to this vision, as they formed the backbone of developing economies yet were subject to volatile prices and unfair trade terms. The NIEO called for structural reforms across trade, finance, debt, technology, transport, and resource management, emphasizing price stabilization, equitable trade, and greater control over natural resources. UNCTAD became the primary forum for advancing the NIEO agenda, starting with UNCTAD IV in Nairobi and continuing through UNCTAD V in Manila and UNCTAD VI in Belgrade. Over roughly a decade, intense negotiations took place across multiple chapters. Dr. Gamani Corea viewed the Integrated Programme for Commodities (IPC) not only as valuable in itself but also as a first step in addressing structural inequalities and market instabilities, to be followed by further transformative measures. Common Fund was conceived as a key mechanism to stabilize commodity markets and support sustainable development, reflecting the NIEO’s broader goals of economic sovereignty and self-determination. It aimed to reduce dependency on industrialized nations and ensure fair returns for commodity producers. The 1974 UN General Assembly Declaration for the Establishment of a New International Economic Order underscored the need for international cooperation to address commodity-related disparities. In the decades since, the CFC has continued to advance the NIEO’s objectives, though challenges remain in fully realizing its vision. The NIEO’s emphasis on commodities as a cornerstone of economic development remains highly relevant, particularly in discussions about sustainable development, fair trade, and addressing persistent structural inequalities in the global economy. |

[1] Pronk, J. (2014). The development consensus. In South Centre, A tribute to Gamani Corea: His life, work and legacy (pp. 78) South Centre.

UNCTAD IV Proceedings, Nairobi

The oil price hike in 1973 by OPEC had a profound impact on non-oil-producing developing countries, significantly straining their balance of payments. This dramatic shift in global oil prices raised broader questions about whether similar collective action could be taken by other commodity producers to stabilize prices and secure fairer trade terms. These concerns, compounded by the economic strain on developing nations, led to critical discussions held from May 5 to 31, 1976, during the fourth session of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD IV) was held in Nairobi, Kenya. The meeting brought together over 2,000 representatives from 153 UNCTAD member states, emphasizing the global significance of the issues at hand.

During the conference, U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger proposed a parallel idea—the creation of an "international resources bank." This proposal aimed to stabilize incomes in commodity-exporting developing nations, focusing on direct private investment through transnational corporations.[1] While Kissinger’s proposal emphasized private capital, it highlighted the shared global recognition of the urgent need for mechanisms addressing commodity price instability.

|

The Kissinger Proposal — International Resources Bank (1976) In April 1976, during his African tour and address to UNCTAD IV in Nairobi, U.S. Secretary of State Henry A. Kissinger proposed an International Resources Bank (IRB) as an alternative to the developing world’s call for a Common Fund for Commodities (CFC). The IRB aimed to mobilize private investment for resource projects, steering the debate away from the solidarity-based financing envisioned in Dr. Gamani Corea’s Integrated Programme for Commodities (IPC), which proposed a USD 11–13 billion fund to stabilize markets for 18 key commodities. Though the IRB never materialized, it marked a turning point in global development finance, symbolizing the shift from collective redistribution toward market-driven, private-capital approaches. Yet both Kissinger’s IRB and Corea’s IPC shared a common premise — that the Global North bore a responsibility to support the Global South’s development. The eventual creation of the Common Fund for Commodities in 1989 carried forward the IPC’s cooperative spirit while adapting to new financial realities. As today’s global trade faces renewed volatility and inequality, the unfinished dialogue between the IRB and CFC visions highlights the ongoing need to balance public purpose with private capital in managing global commodities. Kissinger’s proposal was ultimately rejected by 33 to 31 votes at UNCTAD IV, paving the way for the consensus that led to the CFC — a lasting symbol of shared international responsibility for development. |

[1]https://www.nytimes.com/1976/05/03/archives/kissinger-to-urge-resources-bank-for-third-world.html (Accessed 29 January 2025)

Negotiation Phase

In 1977, discussions intensified around the establishment of the Common Fund under the Integrated Programme for Commodities (IPC). The primary objective was to stabilize prices and enhance earnings for 18 key commodities vital to the economies of developing nations.[1] The Resolution on the Common Fund adopted during the Organization of African Unity's meeting in Libreville, Gabon, from 23rd June to 3rd July 1977, reaffirmed Africa’s unwavering commitment to the Fund and urged unified action among Group of 77 nations. Developing countries heavily reliant on commodity exports strongly supported the initiative, viewing it as a tool for equitable resource distribution and greater influence in the global economic system.

However, developed countries expressed skepticism, they argued that the lack of commodity agreements stemmed from competitive interests and negotiation challenges rather than financial constraints. Many developing countries opposed the fund at the Nairobi conference in 1976.

Conversely, Australia, a significant commodity producer, gradually shifted to support the fund, recognizing potential economic benefits and seeking to strengthen ties with Asian developing countries. Similarly, the Netherlands emerged as the strongest proponent among developed nations, joined by Norway, Sweden, and Denmark, which faced minimal economic risks in supporting the fund. France proposed an alternative, the "Central Fund," as a compromise, however, it differed from the original objectives of the Common Fund.[2]

Prolonged negotiations from 1977 to 1979 were marked by political considerations rather than a primary focus on addressing global poverty. Officials from both developed and developing countries embarked on lengthy discussions to balance domestic pressures and international relations. By March 1979, an agreement was reached on the elements of a Common Fund, including two operational "windows" for stabilizing commodity prices and supporting research and market promotion.

[1] 18 key commodities refer to the IPC; bananas, bauxite, cocoa, coffee, copper, cotton and cotton yarn, hard fibres, iron ore, jute and jute products, manganese, meat, phosphate, rubber, sugar, tea, timber, tin and vegetable oils, including olive oil and oilseeds.

[2] Dell, E. (1986). The Common Fund. International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1944-), 63(1), 21–38. https://doi.org/10.2307/2620230

Formal Adoption and Establishment

The United Nations Negotiating Conference, held under the auspices of UNCTAD, convened in Geneva from June 5 to June 27, 1980. On the final day of the conference, the Agreement establishing the Common Fund was officially adopted. It was opened for signature on 1 October 1980 in New York, with an initial deadline of one year after the fund's entry into force. Despite this milestone, ratifications lagged. A meeting in June 1982 extended the deadline to 30 September 1983, but the necessary requirements for activation were still unmet.

The ratification process was hindered by concerns over the adequacy of proposed funds, unclear objectives, and disagreements over operational control. Developed countries remained divided, with the United States refusing to ratify the agreement, further stalling progress. By January 1986, 90 countries had ratified the agreement, fulfilling the minimum threshold.

Political shifts, including growing pressure from the Carter administration and European Council support, gradually softened opposition. Revisiting the discussions during the London Western Economic Summit of 6-8 May 1977 and CIEC meetings in 1978 highlighted a need for compromise. After further delays, a decision was made to extend the deadline once again to 19 June 1989.[1] Efforts to reconcile differences culminated when the Common Fund was officially established. The fund aimed to stabilize commodity prices, reduce volatility, and support developing nations reliant on primary commodity exports.

[1] Dell, E. (1986). The Common Fund. International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1944-), 63(1), 21–38. https://doi.org/10.2307/2620230

Projects And Implementation

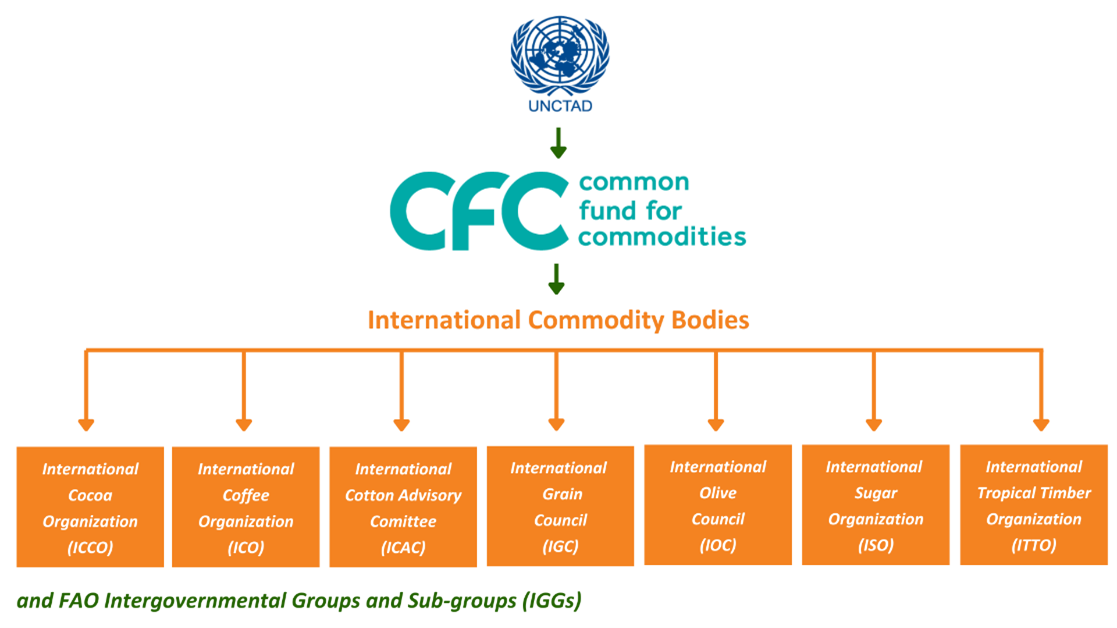

Since 1989, International Commodity Bodies (ICBs) have served as strategic advisors to the Common Fund for Commodities (CFC), guiding its project-based approach to commodity development. These ICBs include major organizations like the International Cotton Advisory Committee (1939), International Rubber Study Group (1944), International Grains Council (1949), International Lead and Zinc Study Group (1959), International Olive Council (1959), International Coffee Organization (1966), International Cocoa Organization (1973), and International Tropical Timber Organization (1986). For commodities not covered by formal ICB structures, the CFC collaborated with the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) through its intergovernmental groups and sub-groups in sectors such as bananas, tropical fruits, grains, oils and fats, hard fibers, meat, and dairy products. These partnerships enabled the Fund to pursue development-oriented cooperation across a wide spectrum of agricultural and non-agricultural commodities.

ICBs evaluate and prioritize project proposals submitted to the CFC, leveraging their expertise in commodity-specific challenges and global trade dynamics. Once projects are approved, the CFC finances and manages their implementation, focusing on tangible outcomes like market stabilization, productivity enhancement, and improved livelihoods for producers. The first commodity development project was approved in 1991. Over the years, they have supported 367 projects addressing key issues in commodity trade, with a total investment of approximately $245.7 million. Of these, 355 projects were grant-based, amounting to $231.8 million, and 12 were loan-based, totaling $13.9 million.

Ongoing Initiatives in Empowering Smallholders

In the decade between the adoption and ratification of the Common Fund for Commodities (CFC), international commodity markets underwent major liberalization. Enthusiasm for binding international commodity agreements (ICAs), central to the Integrated Programme for Commodities (IPC), declined among industrialized nations, and several major ICAs collapsed. As a result, the CFC’s First Account, intended to finance price stabilization through buffer stocks, was never operationalized. Instead, the Fund began by supporting commodity-specific development projects through voluntary contributions to its Second Account, with the first project approved in 1991.

Over time, the CFC evolved toward project-based support rather than price stabilization, prompting some developing countries to request reforms. In December 2014, the Governing Council approved a comprehensive reform package, modernizing the Fund’s financing model and operations. The reforms shifted the CFC from primarily grant-based support to impact investing, introduced "Open Calls for Proposals," emphasized financially viable and sustainable projects, and strengthened partnerships with private-sector actors and NGOs. A Technical Assistance team was also established to provide sector-specific expertise to external investors.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, demand for CFC support surged as smallholders and SMEs faced disrupted supply chains and heightened financial pressures. The Fund’s flexible approach proved essential in targeting support to the most vulnerable, enhancing resilience in commodity-dependent economies, and ensuring resources could be reinvested to maximize impact.

One of the cornerstone initiatives in this new era is the CFC ACT Fund, a $100 million+ impact investment fund activated in September 2025 to support SMEs in developing countries. The Fund is designed to address the critical intersections between smallholder livelihoods, biodiversity preservation, and climate action, thereby reinforcing the CFC’s long-standing mission to empower the world’s most vulnerable communities.

The CFC continues to strengthen its partnerships with international financial institutions (IFIs), development finance institutions (DFIs), other UN bodies, and forward-looking partners committed to advancing inclusive and sustainable growth in commodity-dependent economies. This effort aligns with the CFC Strategic Framework 2025–2035, which lays the foundation for the organization’s next decade of action—championing innovation, resilience, and sustainability across global commodity value chains. Renewed voluntary contributions to the CFC are strategic necessity to continue fulfilling its mandate and evolving in line with its founding principles. The Sevilla Commitment represents a historic reorientation of global development priorities. Paragraph 46(d) explicitly reaffirms the role of the Common Fund for Commodities (CFC):

The Sevilla Outcome (para. 46[d]) frames contributions to the CFC not as charity but as shared obligations under the new global compact, reflecting the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities: while all countries share responsibility for sustainable development, those with greater historical responsibility and economic capacity bear an enhanced duty to support adaptation, resilience, and value addition in the Global South.

Why Smallholders and SMEs are central to the CFC

Smallholders and SMEs are at the heart of the global economy, creating 7 out of 10 jobs worldwide and accounting for 78% of employment in low-income countries.[1] Despite their critical role, 40% of SMEs lack access to $5.2 trillion annually, and smallholders face compounded challenges such as market volatility, climate change, and limited resources.[2]

The CFC empowers these underserved communities through targeted projects and investments like the ACT Fund, aiming to enhance productivity, improve market access, and drive inclusive and sustainable economic growth. These efforts reflect the CFC’s unwavering dedication to addressing inequality and building resilience in commodity-dependent countries.

Why Commodities

Commodities are the backbone of the global economy, underpinning everything from the food we eat to the technology we rely on daily. Approximately 800 million people, many of them at the lowest income levels, depend on commodities and related jobs for their livelihoods.[3] In African Least Developed Countries (LDCs), over 75% rely on commodity production for more than half of their export earnings.[4] Yet, commodity-dependent countries would need an estimated 190 years to halve their reliance compared to other nations.[5]

The global commodity market is vast, the nominal value is projected to grow significantly to $142.85tn by 2025, driven by increasing demand for raw materials, energy, and agricultural products.[6] Despite this growth, the benefits of the commodity market are not evenly distributed. However, without targeted support, smallholders and marginalized communities’ risk being excluded from these gains, unable to access the opportunities created by this growth. This is why organizations like the Common Fund for Commodities (CFC) are crucial. They play a vital role in empowering smallholders, addressing systemic inequalities, and building resilient, sustainable futures.

[1] https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/smefinance (Accessed 29 January 2025)

[2]https://www.weforum.org/stories/2024/08/access-to-credit-slowing-growth-and-development/ (Accessed 29 January 2025)

[3] https://assets.worldbenchmarkingalliance.org/app/uploads/2024/08/Transforming-food-systems-with-small-scale-producers-1.pdf (Accessed 29 January 2025)

[4] https://www.un.org/ldcportal/content/technology-key-transforming-least-developed-countries-heres-how-tesfachew-and-adhikari-world (Accessed 29 January 2025)

[5] https://press.un.org/en/2023/gaef3589.doc.html (Accessed 29 January 2025)

[6] https://www.statista.com/outlook/fmo/commodities/worldwide#value-development (Accessed 29 January 2025)